Prisoner Details : GUCLU AKPINAR Number : Who knows

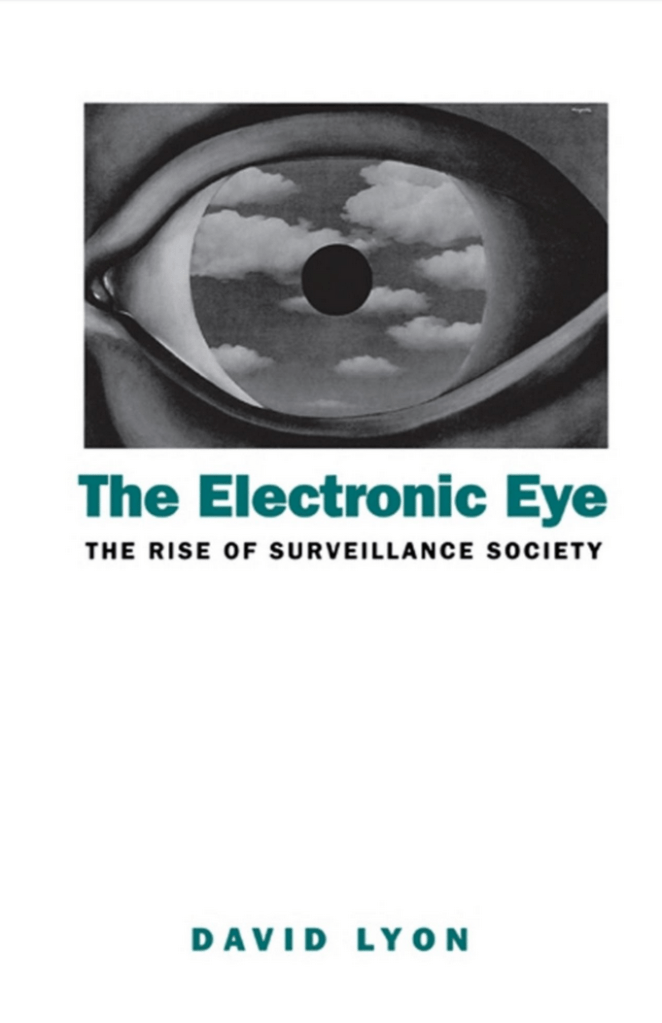

The concept of the “electronic panopticon” is a central theme in David Lyon’s “The Electronic Eye” and draws on the work of French philosopher Michel Foucault, particularly his analysis of panopticism in “Discipline and Punish.” To understand the electronic panopticon, it’s helpful to first examine Foucault’s original concept.

In “Discipline and Punish,” Foucault uses Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon prison design as a metaphor for the operation of power in modern society. The panopticon is a circular prison with a central observation tower, from which a single guard can observe all the inmates without them knowing when they are being watched. The key feature of the panopticon is that inmates internalize the gaze of the guard and begin to police their own behavior, even when they are not being directly observed.

Foucault argues that the panopticon represents a new form of disciplinary power that emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries. Unlike sovereign power, which operates through direct coercion and violence, disciplinary power works by shaping individual behavior and subjectivity through constant surveillance, normalization, and the internalization of discipline.

The panopticon, for Foucault, is not just a specific architectural design, but a general principle of power that can be applied across a range of institutions and social contexts. He argues that the disciplinary techniques of the panopticon have spread throughout society, creating a “carceral archipelago” of institutions (such as schools, hospitals, and factories) that aim to produce docile and useful subjects.

In “The Electronic Eye,” Lyon extends Foucault’s analysis to the contemporary context, arguing that the rise of electronic surveillance technologies has created a new form of panopticism – the electronic panopticon.

Like Foucault’s panopticon, the electronic panopticon operates through the constant surveillance and monitoring of individuals. However, rather than relying on the physical architecture of the prison, the electronic panopticon is created through the use of electronic technologies such as CCTV cameras, databases, computer monitoring, and digital tracking.

Lyon argues that these technologies create a sense of constant visibility and encourage self-monitoring and self-discipline, just as the physical panopticon does. The knowledge that one may be watched at any time leads individuals to internalize the gaze of the watcher and to police their own behavior in accordance with perceived norms and expectations.

However, the electronic panopticon also differs from Foucault’s original concept in several key ways, while the panopticon relies on a central observation tower, the electronic panopticon is decentralized and diffuse. Surveillance is carried out through a network of technologies and institutions, often without a clear center of control. The electronic panopticon relies heavily on automated systems for data collection, analysis, and decision-making. This automation increases the scale and efficiency of surveillance, but also raises questions about accountability and transparency. Unlike the physical panopticon, where the presence of the central tower is a constant reminder of surveillance, the electronic panopticon is often invisible and operates in the background of everyday life. This invisibility can make it difficult for individuals to know when and how they are being monitored.

In the electronic panopticon, individuals are not just passive subjects of surveillance, but also active participants. Through the use of social media, mobile devices, and other technologies, individuals actively share personal information and contribute to their own surveillance.

The electronic panopticon represents a significant erosion of privacy, as more and more aspects of personal life are subject to monitoring and data collection. Lyon argues that privacy is not just an individual right, but a social value that is essential for the development of autonomy, creativity, and dissent.

The electronic panopticon also raises concerns about social sorting and discrimination. Surveillance data can be used to categorize and profile individuals, leading to differential treatment based on factors such as race, class, gender, and sexuality.

he knowledge that one is being watched can have a chilling effect on behavior, leading individuals to conform to perceived norms and expectations. This can stifle creativity, dissent, and political engagement, undermining the vitality of democratic societies.

The electronic panopticon reflects and reinforces power asymmetries in society, as those with access to surveillance data (such as government agencies and private corporations) have greater power to monitor and control the behavior of others.

The electronic panopticon is driven in part by the commercial value of personal data, leading to the commodification of privacy. Lyon argues that this commodification turns personal information into a marketable asset, undermining individual control over one’s own data.

Despite these concerns, Lyon also recognizes the potential benefits of electronic surveillance in certain contexts, such as enhancing public safety or improving organizational efficiency. However, he argues that these benefits must be weighed against the social and political costs of surveillance, and that the use of surveillance must be subject to democratic oversight and regulation.

Lyon also suggests that resistance to the electronic panopticon is possible and necessary. This resistance can take many forms, from individual practices of privacy protection (such as using encryption or avoiding certain technologies), to collective action and advocacy for privacy rights and surveillance regulation.

Since the publication of “The Electronic Eye” in 1994, the scope and sophistication of electronic surveillance has only grown. The rapid development of technologies such as the internet, mobile devices, social media, and artificial intelligence has created new opportunities for data collection and analysis, and has made surveillance an increasingly pervasive feature of everyday life.

In this context, Lyon’s analysis of the electronic panopticon remains highly relevant. The concerns he raises about privacy, discrimination, chilling effects, and power asymmetries are more pressing than ever, as surveillance becomes more automated, invisible, and participatory.

While recognizing the potential benefits of surveillance in certain contexts, Lyon calls for greater public awareness and debate about the social and political costs of the electronic panopticon, and for the development of legal and ethical frameworks to regulate and limit surveillance practices.

Ultimately, the concept of the electronic panopticon reminds us of the need to interrogate the power relations and social implications of the technologies we create and use. It calls on us to imagine and work towards a society in which the benefits of technology are balanced with the protection of human dignity, autonomy, and democratic values.