Introduction

Human networks form the backbone of our social existence, shaping everything from our personal relationships to global socio-economic systems. These networks operate on multiple scales, from intimate family units to vast international connections, each with its own unique characteristics and dynamics. Understanding the scale of these networks and how individuals—or “nodes”—interact within and between them is crucial for comprehending human behavior, social structures, and the flow of information and resources in our increasingly interconnected world.

This essay explores the multifaceted nature of human networks, examining their scales, structures, and the intricate interactions that occur between different network levels. We will delve into the theoretical frameworks that underpin our understanding of these networks, analyze real-world examples of network dynamics, and consider the implications of these interactions for various aspects of human society.

Outline

- Scales of Human Networks 1.1 Micro-level Networks 1.2 Meso-level Networks 1.3 Macro-level Networks 1.4 Global Networks

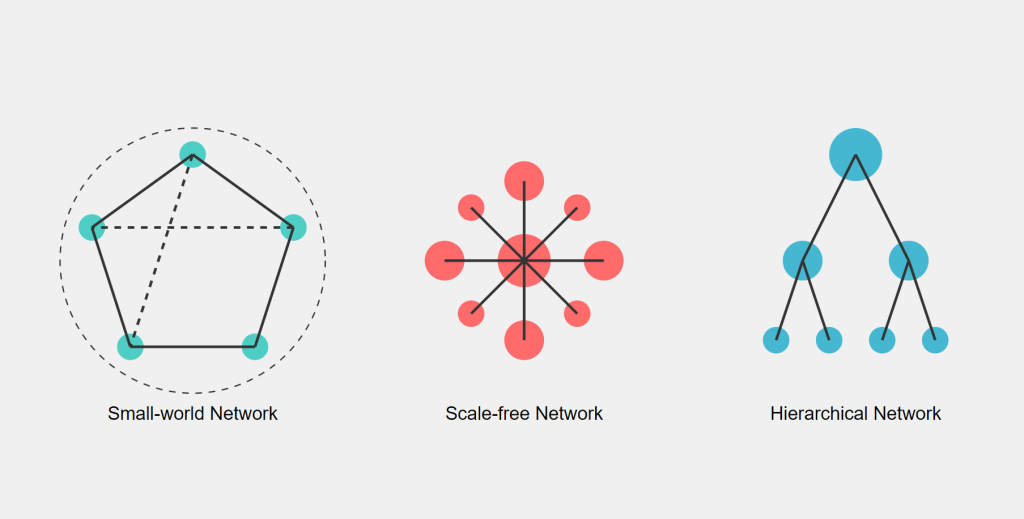

- Network Structures and Properties 2.1 Small-world Networks 2.2 Scale-free Networks 2.3 Hierarchical Networks

- Interactions Between Network Nodes 3.1 Strong and Weak Ties 3.2 Bridging and Bonding Social Capital 3.3 Homophily and Heterophily

- Cross-Network Interactions 4.1 Information Flow Across Network Boundaries 4.2 Resource Exchange Between Networks 4.3 Cultural Diffusion Through Network Interactions

- Impact of Technology on Human Networks 5.1 Social Media and Digital Networks 5.2 Global Communication Platforms 5.3 Virtual Communities and Online Identities

- Applications and Implications 6.1 Social Influence and Opinion Formation 6.2 Innovation Diffusion and Adoption 6.3 Collective Action and Social Movements 6.4 Public Health and Disease Spread

- Challenges and Future Directions 7.1 Privacy and Security in Networked Societies 7.2 Network Resilience and Adaptability 7.3 Ethical Considerations in Network Analysis

- Conclusion

Now, let’s proceed with the first section of the essay:

1. Scales of Human Networks

Human networks exist on various scales, each with distinct characteristics and functions. Understanding these scales is crucial for comprehending the complexity of human social structures and interactions.

1.1 Micro-level Networks

Micro-level networks represent the most intimate and immediate social connections in an individual’s life. These networks typically consist of 5 to 15 people and include close family members, romantic partners, and best friends. Dunbar’s number, proposed by anthropologist Robin Dunbar, suggests that humans can maintain stable social relationships with approximately 150 people, but the innermost circle is much smaller (Dunbar, 1992).

Micro-level networks are characterized by:

- High emotional intensity

- Frequent interactions

- Strong trust and reciprocity

- Shared personal information and resources

These networks play a crucial role in an individual’s emotional well-being, personal development, and daily support system. They often serve as the primary source of emotional support, practical assistance, and intimate social interaction.

Example: A nuclear family unit, consisting of parents and children, represents a typical micro-level network. Within this network, members share deep emotional bonds, engage in daily interactions, and rely on each other for various forms of support.

1.2 Meso-level Networks

Meso-level networks expand beyond the intimate circle to include extended family, friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. These networks typically range from 50 to 150 individuals, aligning with Dunbar’s number for stable social relationships (Dunbar, 1998).

Characteristics of meso-level networks include:

- Moderate emotional intensity

- Regular but less frequent interactions

- Varied levels of trust and reciprocity

- Shared interests or contexts (e.g., workplace, community)

Meso-level networks are essential for:

- Professional development and career opportunities

- Access to diverse information and resources

- Community engagement and social integration

- Expanding one’s social capital

Example: A person’s workplace network, including immediate team members, other departments, and casual work acquaintances, forms a meso-level network. These connections provide professional support, career opportunities, and a sense of belonging within the organizational context.

1.3 Macro-level Networks

Macro-level networks encompass larger social structures, including communities, organizations, and entire cities or regions. These networks can consist of thousands to millions of individuals and are often characterized by indirect connections and shared cultural or societal contexts.

Key features of macro-level networks:

- Low emotional intensity on an individual level

- Infrequent or indirect interactions between most members

- Shared cultural, societal, or institutional frameworks

- Complex organizational structures and hierarchies

Macro-level networks influence:

- Social norms and cultural practices

- Economic systems and market dynamics

- Political processes and governance

- Large-scale collective behaviors

Example: A city’s population forms a macro-level network, where individuals are connected through shared urban infrastructure, local government, and cultural identity. While most city residents may never interact directly, they are part of a larger network that shapes their daily lives and experiences.

1.4 Global Networks

At the largest scale, global networks connect individuals and groups across national and continental boundaries. These networks have become increasingly prominent and influential with the advent of globalization and digital communication technologies.

Characteristics of global networks include:

- Vast scale, potentially encompassing billions of people

- Highly diverse participants from various cultures and backgrounds

- Primarily mediated interactions (e.g., through technology)

- Complex interdependencies and far-reaching impacts

Global networks impact:

- International trade and economic systems

- Global governance and diplomacy

- Cultural exchange and hybridization

- Worldwide information flow and knowledge sharing

Example: The internet itself represents a global network, connecting billions of users worldwide. Social media platforms like Facebook or Twitter create global networks where information can spread rapidly across continents, influencing public opinion, consumer behavior, and even political movements on a global scale.

Understanding these different scales of human networks provides a foundation for analyzing how individuals interact within and between these networks. In the following sections, we will explore the structures and properties of these networks, as well as the dynamics of node interactions that shape our complex social world.

The Scale of Human Networks and Interactions of Human Nodes Between Different Human Networks

2. Network Structures and Properties

Understanding the structures and properties of human networks is crucial for analyzing how they function and evolve. These characteristics influence information flow, resource distribution, and the overall dynamics of social interactions. This section explores three key network structures commonly observed in human social systems: small-world networks, scale-free networks, and hierarchical networks.

Small-world Network:

- 3D Appearance: Imagine a sphere with many nodes distributed evenly on its surface. Most connections are between nearby nodes, but a few long-range connections create shortcuts across the sphere.

- Real-world Example: The network of actors in Hollywood. Most actors are connected to those they’ve worked with directly, but a few well-connected actors create shortcuts across the entire industry.

Scale-free Network:

- 3D Appearance: Picture a structure with a few large hub nodes at the center, each connected to many smaller nodes. These smaller nodes have fewer connections, creating a hierarchy of connectivity.

- Real-world Example: The World Wide Web. A few highly popular websites (like Google or Facebook) act as hubs, connected to many smaller websites.

Hierarchical Network:

- 3D Appearance: Envision a tree-like structure in 3D space. At the top is a single node, branching out to multiple nodes below it, which in turn branch out further, creating distinct levels.

- Real-world Example: Corporate organizational structures. The CEO is at the top, connected to department heads, who are connected to managers, who are connected to individual contributors.

2.1 Small-world Networks

Small-world networks, first introduced by Watts and Strogatz (1998), are characterized by high clustering coefficients and short average path lengths. In human terms, this means that most nodes (individuals) in the network are not directly connected, but can be reached through a relatively small number of intermediary connections.

Key features of small-world networks include:

- High local clustering: Individuals tend to form tight-knit groups with their immediate connections.

- Short global separation: Any two individuals in the network can be connected through a small number of intermediary links.

- The “six degrees of separation” phenomenon: The idea that any two people on Earth are connected by at most six social connections.

Implications for human networks:

- Efficient information spread: News, ideas, and innovations can propagate quickly through the network.

- Social cohesion: Local clusters foster strong community ties while maintaining global connectivity.

- Resilience: The network remains connected even if some nodes or links are removed.

Example: A study by Milgram (1967) demonstrated the small-world property in human social networks by asking participants to forward a package to a target person through their acquaintances. The packages that reached their destinations typically passed through only about six intermediaries, giving rise to the “six degrees of separation” concept.

2.2 Scale-free Networks

Scale-free networks, introduced by Barabási and Albert (1999), are characterized by a power-law degree distribution. In these networks, a small number of nodes have a very high number of connections, while most nodes have only a few connections.

Key features of scale-free networks:

- Presence of hubs: Highly connected nodes that act as central points in the network.

- Preferential attachment: New nodes are more likely to connect to already well-connected nodes.

- Power-law degree distribution: The probability of a node having k connections is proportional to k^(-γ), where γ is typically between 2 and 3.

Implications for human networks:

- Efficient navigation: Hubs facilitate quick traversal of the network.

- Vulnerability to targeted attacks: Removing hub nodes can significantly disrupt the network.

- Emergence of influencers: Highly connected individuals can have disproportionate impact on information flow and opinion formation.

Example: Social media networks often exhibit scale-free properties. On platforms like Twitter, a small number of users (celebrities, politicians, organizations) have millions of followers, while the majority of users have relatively few connections.

2.3 Hierarchical Networks

Hierarchical networks combine elements of both small-world and scale-free networks, featuring a modular structure with hierarchically organized communities. These networks are particularly relevant to human social structures, which often involve nested levels of organization.

Key features of hierarchical networks:

- Modular structure: The network is composed of interconnected modules or communities.

- Self-similarity: Similar patterns of organization repeat at different scales within the network.

- Hierarchical organization: Modules are organized into larger modules, forming a tree-like structure.

Implications for human networks:

- Efficient local and global communication: Information can spread quickly within modules and between different levels of the hierarchy.

- Adaptability: The modular structure allows for localized changes without disrupting the entire network.

- Complex social dynamics: Interactions can vary significantly depending on the hierarchical level and module membership.

Example: Corporate structures often resemble hierarchical networks, with teams forming modules, departments forming larger modules, and so on up to the executive level. This structure facilitates both specialized work within teams and coordination across the organization.

Understanding these network structures provides insights into how human social systems organize and function. Small-world properties explain the interconnectedness of global society, scale-free characteristics shed light on the emergence of social influencers, and hierarchical structures reflect the complex, nested nature of many human organizations.

These network properties have profound implications for various social phenomena, including:

- Information diffusion: The speed and reach of information spread in different types of networks.

- Social influence: How ideas, behaviors, and trends propagate through society.

- Organizational design: Optimal structures for different types of human collectives.

- Resilience and adaptability: How networks respond to changes, disruptions, or targeted interventions.

In the next section, we will explore how individual nodes (people) interact within these network structures, focusing on the concepts of strong and weak ties, social capital, and the principles of homophily and heterophily.

3. Interactions Between Network Nodes

The dynamics of human networks are largely determined by how individual nodes (people) interact with one another. This section explores key concepts that shape these interactions: strong and weak ties, social capital, and the principles of homophily and heterophily.

3.1 Strong and Weak Ties

Granovetter’s (1973) seminal work on the strength of weak ties highlighted the importance of different types of connections in social networks.

Strong ties:

- Characterized by frequent interaction, emotional intensity, and reciprocal services

- Typically found in close relationships (family, close friends)

- Provide emotional support and readily share resources

Weak ties:

- Characterized by infrequent interaction and lower emotional intensity

- Often connect individuals from different social circles

- Act as bridges between different network clusters

Implications:

- Information flow: Weak ties often provide access to novel information and opportunities not available within one’s immediate social circle.

- Social cohesion: Strong ties foster trust and cooperation within communities.

- Career advancement: Weak ties have been shown to be particularly valuable in job searches and professional networking (Granovetter, 1995).

3.2 Bridging and Bonding Social Capital

Social capital refers to the resources and benefits individuals can access through their social networks. Putnam (2000) distinguished between two types of social capital:

Bonding social capital:

- Develops within homogeneous groups

- Strengthens in-group identity and support

- Facilitates reciprocity and mobilization of solidarity

Bridging social capital:

- Develops between diverse groups

- Facilitates access to external assets and information diffusion

- Crucial for social mobility and community development

Implications:

- Community resilience: A balance of bonding and bridging social capital contributes to community adaptability and resilience.

- Social integration: Bridging capital is essential for integrating diverse groups within larger social structures.

- Economic outcomes: Both forms of social capital can influence economic success at individual and community levels.

3.3 Homophily and Heterophily

Homophily, the tendency of individuals to associate with similar others, and heterophily, the attraction to different others, play crucial roles in shaping network structures and interactions.

Homophily:

- Based on shared characteristics (e.g., age, ethnicity, education, interests)

- Leads to the formation of homogeneous social clusters

- Facilitates trust and mutual understanding

Heterophily:

- Attraction to individuals with different characteristics

- Promotes diversity in social networks

- Facilitates exposure to new ideas and perspectives

Implications:

- Network segregation: Strong homophily can lead to isolated social clusters, potentially reinforcing social divides.

- Innovation: Heterophilous connections often drive innovation by exposing individuals to diverse ideas and practices.

- Social influence: Homophilous ties may be more influential in changing attitudes and behaviors.

Understanding these interaction dynamics is crucial for analyzing how information, resources, and influence flow through human networks. The balance between strong and weak ties, the development of different forms of social capital, and the interplay between homophily and heterophily shape the structure and function of social networks at all scales.

4. Cross-Network Interactions

As individuals participate in multiple networks simultaneously, understanding how these networks interact and influence each other becomes crucial. This section explores the dynamics of cross-network interactions, focusing on information flow, resource exchange, and cultural diffusion.

4.1 Information Flow Across Network Boundaries

Information rarely remains confined to a single network. The transmission of knowledge, news, and ideas across network boundaries is a key feature of human social systems.

Key aspects:

- Boundary spanners: Individuals who belong to multiple networks and facilitate information transfer between them.

- Structural holes: Gaps between non-redundant contacts that provide opportunities for information brokerage (Burt, 2004).

- Cascading effects: Information that gains traction in one network can rapidly spread to connected networks.

Implications:

- Innovation diffusion: Cross-network information flow is crucial for the spread of new ideas and technologies.

- Public opinion formation: The interaction of different information ecosystems shapes broader societal views.

- Organizational learning: Companies benefit from employees who can access and integrate information from diverse networks.

4.2 Resource Exchange Between Networks

Networks serve as conduits not only for information but also for tangible and intangible resources.

Types of resources exchanged:

- Material resources (e.g., goods, money)

- Social support (e.g., emotional support, advice)

- Opportunities (e.g., job openings, business partnerships)

Mechanisms of exchange:

- Reciprocity: The expectation of future returns drives resource sharing.

- Reputation effects: Resource provision can enhance one’s standing across multiple networks.

- Institutional frameworks: Formal structures (e.g., trade agreements) facilitate inter-network resource flows.

Implications:

- Economic resilience: Diverse inter-network resource exchanges can buffer against localized scarcities.

- Social safety nets: Cross-network support systems provide individuals with varied sources of assistance.

- Power dynamics: Control over resource flows between networks can be a source of influence and power.

4.3 Cultural Diffusion Through Network Interactions

The interaction of different networks facilitates the spread and evolution of cultural elements.

Processes of cultural diffusion:

- Direct transfer: Adoption of cultural practices or beliefs from one network to another.

- Hybridization: Blending of cultural elements from different networks to create new forms.

- Resistance and adaptation: Selective adoption or modification of cultural elements to fit local contexts.

Factors influencing cultural diffusion:

- Network permeability: The ease with which cultural elements can cross network boundaries.

- Cultural compatibility: The degree to which new elements align with existing cultural frameworks.

- Power differentials: Dominant networks may exert greater cultural influence on subordinate ones.

Implications:

- Globalization: Increased inter-network interactions accelerate global cultural exchange.

- Identity formation: Exposure to diverse cultural influences shapes individual and group identities.

- Social cohesion: Shared cultural elements across networks can foster broader social integration.

Understanding cross-network interactions provides insights into the complex dynamics of our interconnected world. These interactions shape the flow of information, resources, and cultural elements, influencing everything from individual decision-making to global trends.

5. Impact of Technology on Human Networks

Technological advancements, particularly in digital communication, have profoundly reshaped human networks. This section examines how technology has transformed network structures, interactions, and the very nature of human connectivity.

5.1 Social Media and Digital Networks

Social media platforms have created new forms of networks that transcend traditional spatial and temporal constraints.

Key features:

- Scalability: Ability to maintain much larger networks of weak ties.

- Persistence: Digital interactions leave lasting traces, affecting network dynamics over time.

- Searchability: Easy discovery of like-minded individuals or communities.

Implications:

- Network expansion: Individuals can maintain larger, more diverse personal networks.

- Echo chambers: Tendency for users to cluster in ideologically homogeneous groups.

- Influencer culture: Emergence of highly central nodes with disproportionate network influence.

5.2 Global Communication Platforms

Technologies like instant messaging, video conferencing, and collaborative tools have redefined how networks operate across geographical boundaries.

Impact on networks:

- Compression of space and time: Real-time communication regardless of physical distance.

- Democratization of network formation: Reduced barriers to creating and joining global networks.

- Hybrid networks: Blending of online and offline interactions within network structures.

Implications:

- Globalization of work: Rise of distributed teams and remote work arrangements.

- Transnational communities: Formation of networks based on shared interests rather than geographic proximity.

- Information velocity: Accelerated spread of information (and misinformation) across global networks.

5.3 Virtual Communities and Online Identities

Digital platforms enable the creation of virtual communities and the construction of online identities, adding new dimensions to human networks.

Characteristics:

- Anonymity and pseudonymity: Ability to participate in networks with varying degrees of identity disclosure.

- Multiplicity of identities: Individuals can maintain different personas across various online networks.

- Niche communities: Formation of highly specialized networks around specific interests or identities.

Implications:

- Identity exploration: Online networks provide spaces for identity experimentation and expression.

- Social support: Virtual communities can offer valuable support, especially for marginalized groups.

- Trust and verification challenges: Managing authenticity and trust in online network interactions.

The technological transformation of human networks has far-reaching consequences for social structures, information flow, and individual behavior. While offering unprecedented connectivity and opportunities for network formation, these changes also present new challenges in managing information overload, privacy, and the quality of social connections.

6. Applications and Implications

The study of human networks and their interactions has wide-ranging applications across various domains. This section explores how network understanding informs social influence, innovation diffusion, collective action, and public health strategies.

6.1 Social Influence and Opinion Formation

Network structures play a crucial role in how opinions form and spread through society.

Key concepts:

- Opinion leaders: Influential nodes that shape the views of their network neighbors.

- Threshold models: The idea that individuals adopt opinions when a certain proportion of their network has done so (Granovetter, 1978).

- Information cascades: Rapid spread of opinions or behaviors through a network.

Applications:

- Marketing: Identifying influential nodes for targeted advertising campaigns.

- Political campaigning: Understanding how political opinions form and spread through social networks.

- Combating misinformation: Developing strategies to counteract the spread of false information in networks.

6.2 Innovation Diffusion and Adoption

The structure of human networks significantly influences how innovations spread and are adopted.

Factors affecting diffusion:

- Network density: Denser networks may facilitate faster initial spread but slower overall adoption.

- Structural diversity: Exposure to diverse network segments can accelerate adoption of beneficial innovations.

- Change agents: Individuals who actively promote innovation within their networks.

Applications:

- Product launches: Optimizing market entry strategies based on network characteristics.

- Technology adoption: Predicting and influencing the uptake of new technologies.

- Organizational change: Managing the diffusion of new practices within company networks.

6.3 Collective Action and Social Movements

Network structures can facilitate or hinder the organization of collective action.

Network effects on collective action:

- Mobilization capacity: Dense networks can rapidly mobilize resources and participants.

- Frame alignment: How easily collective action frames spread through network structures.

- Resilience to repression: Decentralized networks may be more resilient to targeted disruption.

Applications:

- Grassroots organizing: Leveraging network structures for effective community mobilization.

- Online activism: Understanding how digital networks facilitate new forms of collective action.

- Conflict resolution: Identifying key network nodes for mediating conflicts between groups.

6.4 Public Health and Disease Spread

Network analysis is crucial for understanding and managing the spread of diseases.

Network factors in epidemiology:

- Contact patterns: How network structures influence disease transmission rates.

- Super-spreaders: Highly connected individuals who play a disproportionate role in disease spread.

- Community structures: How network modularity affects the containment of outbreaks.

Applications:

- Epidemic modeling: Developing more accurate models of disease spread based on network dynamics.

- Vaccination strategies: Optimizing immunization programs by targeting key network nodes.

- Health communication: Leveraging network structures to disseminate health information effectively.

Understanding human networks and their interactions provides valuable insights across these diverse domains. By applying network principles, researchers and practitioners can develop more effective strategies for influencing social outcomes, spreading innovations, organizing collective action, and managing public health challenges.

7. Challenges and Future Directions

As our understanding of human networks deepens and technology continues to reshape social interactions, several challenges and opportunities emerge. This section explores key issues facing network researchers and practitioners, as well as potential future directions for the field.

7.1 Privacy and Security in Networked Societies

The increasing interconnectedness of human networks raises significant privacy and security concerns.

Challenges:

- Data protection: Safeguarding personal information in highly connected networks.

- Surveillance: Balancing security needs with individual privacy rights.

- Digital footprints: Managing the long-term implications of persistent online network activities.

Future directions:

- Privacy-preserving network analysis techniques

- Decentralized network architectures that enhance user control over data

- Ethical frameworks for network data collection and analysis

7.2 Network Resilience and Adaptability

Understanding how networks respond to disruptions and changing environments is crucial for building resilient social systems.

Key areas of focus:

- Robustness to node/link failures: How networks maintain functionality when components are removed.

- Adaptive capacity: The ability of networks to reconfigure in response to external pressures.

- Cascading failures: Understanding and mitigating the risk of system-wide collapses.

Future directions:

- Developing predictive models of network resilience

- Designing intervention strategies to enhance network adaptability

- Exploring the role of diversity in network resilience

7.3 Ethical Considerations in Network Analysis

The power of network analysis tools raises important ethical questions about their use and potential misuse.

Ethical challenges:

- Informed consent: Ensuring individuals are aware of how their network data is used.

- Algorithmic bias: Addressing biases in network analysis algorithms that may perpetuate social inequalities.

- Dual-use concerns: Managing the potential for network analysis tools to be used for harmful purposes.

Future directions:

- Developing ethical guidelines for network research and applications

- Increasing transparency in network analysis methodologies

- Exploring participatory approaches to network analysis that involve communities in the research process

7.4 Integration of Multiple Data Sources

As data sources proliferate, integrating diverse types of network data presents both opportunities and challenges.

Areas of development:

- Multi-layer network analysis: Combining different types of network data (e.g., social, physical, digital) for more comprehensive understanding.

- Real-time network monitoring: Developing techniques for analyzing dynamic network data streams.

- Cross-disciplinary data integration: Combining network data with insights from fields like psychology, economics, and neuroscience.

Future directions:

- Advanced data fusion techniques for network analysis

- Development of standardized protocols for network data sharing and integration

- Exploration of machine learning approaches for handling complex, multi-dimensional network data

7.5 Scaling Network Analysis

As human networks grow in size and complexity, scaling analysis techniques becomes increasingly important.

Challenges:

- Computational limitations: Developing algorithms that can handle massive network datasets.

- Visualization: Creating meaningful visualizations of large-scale network structures.

- Temporal dynamics: Analyzing how large networks evolve over time.

Future directions:

- Quantum computing applications for network analysis

- Advanced network sampling techniques for analyzing large-scale networks

- Development of new metrics and measures for characterizing complex network structures

As the field of human network analysis continues to evolve, addressing these challenges and exploring new directions will be crucial. The insights gained from this work have the potential to significantly enhance our understanding of human social systems and inform strategies for addressing complex societal challenges.

8. Conclusion

The study of human networks and the interactions between network nodes provides a powerful lens through which to understand the complexities of human social systems. From the intimate scale of personal relationships to the vast expanse of global interconnections, network structures shape and are shaped by human behavior, information flow, and resource distribution.

Key insights from this exploration include:

- The multi-scale nature of human networks, ranging from micro-level personal connections to macro-level societal structures and global networks.

- The importance of network structures such as small-world, scale-free, and hierarchical networks in determining how information and resources flow through social systems.

- The crucial role of different types of ties (strong and weak) and forms of social capital (bonding and bridging) in facilitating various social processes.

- The impact of homophily and heterophily on network formation and the implications for social cohesion and innovation.

- The transformative effect of technology on human networks, creating new forms of connectivity and reshaping traditional network dynamics.

- The wide-ranging applications of network analysis in areas such as social influence, innovation diffusion, collective action, and public health.

- The emerging challenges and future directions in network research, including privacy concerns, network resilience, ethical considerations, and the need for advanced analytical techniques.

As we continue to navigate an increasingly interconnected world, the importance of understanding human networks only grows. The insights gained from network analysis have the potential to inform more effective strategies for addressing complex social issues, from improving public health outcomes to fostering social cohesion in diverse communities.

However, with this power comes responsibility. As researchers and practitioners in this field, we must remain mindful of the ethical implications of our work and strive to develop approaches that respect individual privacy while harnessing the collective intelligence of human networks.

The future of human network research promises exciting developments, particularly as we integrate insights from diverse disciplines and leverage advancing technologies. By continuing to deepen our understanding of how human nodes interact within and across different network scales, we can work towards creating more resilient, equitable, and thriving social systems.